How a 90s childhood memory turned dad joke inspired a simple philosophy for building great products and relationships.

Earlier this year, my aunt passed away. While we weren’t close, a few things had always stuck with me from childhood when she babysat my younger sister and me. One was her adoration for the Cincinnati Bengals. Growing up, my family lived close to Pittsburgh and were all raised to be citizens of Steeler Nation. It was the late 80s, and I guess her love of Garfield and crush on Boomer Esiason clarified her allegiance, albeit controversial.

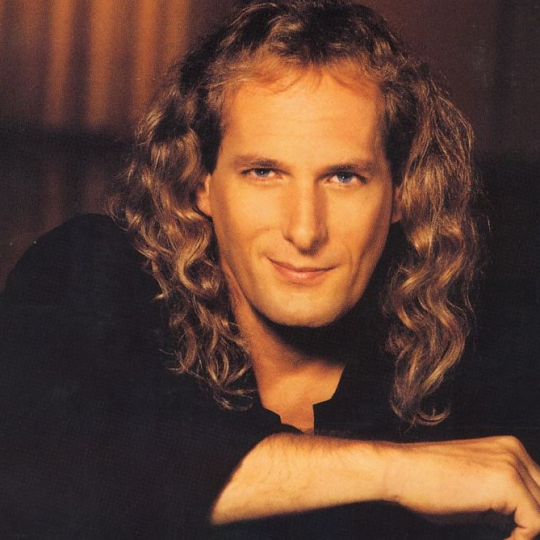

The other memory burn was my aunt’s near-continuous play of Michael Bolton’s 1991 album Time, Love, and Tenderness. Specifically, the title track—the sound of which was offensive to my then 12-year-old ears and still not my cup of tea today. Even if you don’t celebrate the guy’s entire catalog, you might be a parent like me who recently did a double take when listening to their kid’s favorite cartoon. After all these years, he’s still got that buttery baritone, and it still takes me back.

In our internal Slacks and team meetings, I’ve joked on more than one occasion that good work requires a Michael Bolton mindset principled on time, love, and tenderness. As you might imagine, it garnered the chuckles I anticipated from my Gen X colleagues and the confusion I expected from my Gen Z ones. But if you indulge me, I think there’s more truth to it than I realized.

Time

In business, time is money. But not taking enough time upfront can cost much more. Taking strategic time at the beginning of a project through stakeholder interviews, customer research, or collaborative activities like persona and journey workshops pay dividends through the clarity of focus they give the team. Trust me; this allows everything that follows to move faster and with conviction. Confidence begets confidence.

Time early on can do the same for the visual component of digital product work. Working through and agreeing on the foundational tenets of aesthetics and interaction from the start can create the conditions for more high-fidelity prototypes in front of customers (awesome) and expedited delivery to development (awesomer). Spark uses a sprint-based structure for most projects, and our internal and client devs love us for it.

Love

Love is all about honesty. We think about our clients and their products as long-term relationships. Some of my biggest regrets professionally are when I didn’t speak up enough when I felt a client’s strategy or decision wasn’t right. And just like in real life, you’re probably in a bad relationship if you, your team, or the client can’t take or deliver a little tough love.

Love is also about passion. Designers, developers, and business owners are all driven to make something great. And it’s the collision of those diverse skills, enthusiasm, and expertise that have the potential to create something unique. That’s the power of love. Which is also a song from my childhood, but I digress.

Tenderness

Most days, we’re working to make the thing in front of us and those around us—including ourselves, better. Approaching situations with kindness can improve mood and self-esteem while building one of the most critical attributes of an experience designer—empathy. Kindness can unlock a deeper understanding of the motivations of the individuals we work with and the people we design for.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Kindness isn’t tenderness, and I agree. By definition, tenderness drifts into something more profound and too romantic for what I’m trying to do here. But given you’ve read this far, you’ve probably already forgiven me because you’re the type of person who’d be (wait for it) kind.

There you have it. Unsurprisingly, probably to my late aunt most of all, Michael Bolton continues to have relevance. So, in closing, I want to thank her posthumously for the inspiration and leave you with a revised take on the track’s lyrical wisdom:

When work puts you through the fire

When a project puts you to the test

Nothing cures a broken user experience

Like time, love, and tenderness